Bio

Bahram Khayat, a native-born of Tehran, Iran, was introduced to the world of music at the age of ten by his brother.

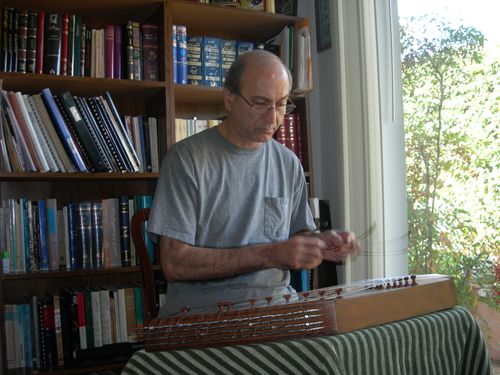

He later entered the School of National Music (SNM) in Tehran, with the Santúr as his instrument of choice. For a period of 3 1/2 years, he learned maestro ‘Abul-Hassan Sabá’s Scales (Radíf) of Persian Music under the instruction of Dr. Manuchehr Sadeghí, who played a major role in training and encouraging this young pupil.

When Amir Jahed, the headmaster of the SNM, established an orchestra consisting of the school’s most outstanding students, Khayát was selected to play the santúr. He was among those who received an award from Iran’s Minister of Culture and Art for his exceptional performance.

He found this incongruent with his quest for rendering his music in an unadulterated form and decided to withdraw from public performances.

Encouraged by this lofty goal, he resumed his research by staying connected with the state of music in his motherland, and by delving into the works of the old Persian music masters. In the meantime, he began to teach his music to young talent in the southern California area.

After several years of diligent work in search of finding the true essence of Classical Persian music, particularly its spiritual properties, Khayát found his much sought-after enlightenment, thus further illuminating his musical inspirations.

His accomplishments culminated in authoring his recently published book, Shogh-i-Nahan, The Hidden Desire, and recording a number of solo performances presented in part in this CD recording.

Khayat is among the few remaining Persian musicians abroad who meticulously kept his music inspirations unaffected by the West and purely traditional. The purpose of this CD is to contribute to the safeguarding and the integrity of this traditional music, the music which has survived a number of devastating cultural invasions throughout the history, all the while remaining as one of the richest traditional music of the world.

The work of some of the contemporary Persian musical composers in the West as well as in the East has become either repetitive, stagnant or deviated from the traditional norm in their musical compositions by surrendering to Western influences.

Khayat, on the other hand, is one of the few who has diligently preserved the integrity of this rich traditional music and has composed numerous innovative and dynamic rhythms not heard to date in the West. While maintaining a strict dedication to the music of Iran, he takes pride in taking such a firm and unrelenting position and feels confident in accomplishing his ultimate goal of maintaining the purity of Iranian Classical music in the West.

It was the early part of the 1980’s that maestro Faramarz Páyvar visited Los Angeles. Although quite known for his high standards and difficult-to-please approach to art, he seldom allowed newcomers in to his circle and welcomed their expression of their artistic work, yet he, upon meeting Bahrám, was won over and welcomed his innate performance and mastery of the instrument, a quality which, in my estimation, Páyvar was delighted to discover. Maestro Páyvar spent nearly a year with Bahrám on a daily basis, collaborating and teaching many long hours at a time, which I was privileged to be in their company but only for a few days.

Now the mystery of Bahrám’s work: it was toward the latter days of the Qajár dynasty when the French government presented a piano to the Sháh as a gift. Sururu’l-Mulk, the santúr maestro of the royal court, was the first person to tune this piano within the Persian Classical modes. In his performances of the piano, he thus imposed santúr techniques to this western instrument, similar to the relationship that eventually developed between Kamáncheh (fiddled spike) and the violin. It was the work of Mushír Homáyún-i-Shahrdár, a prominent student of Sururu’l-Mulk, that greatly shaped and influenced Bahram’s study, thus creating a new style in santúr performance.

One of the notable aspects of Bahrám is that he never manifests any satisfaction and completeness about his body of work. Thus he infuses a fresh zest and life to his composition constantly. In regards to his teaching abilities, he is peerless. He considers his time with his students and effort spent with them as an honor and privilege, exemplifying a superb selflessness. His approach to teaching is such that he never tires or yields to his pupil’s handicap until they have overcome them. His exemplary students are so well versed in his teachings that in times of necessity for substitution, they convey Bahram’s instructions verbatim such that the pupil never feels the absence of their maestro.

Khayat moved to southern, California in 1975, where he continued his extensive research into the intricacies and hidden nuances of traditional Persian Music. In 1984 maestro Payvar came to the U.S. and took residence in Los Angeles for a year, this gave Khayát the opportunity to resume his daily, in-depth lessons, marked by intensively long hours, with maestro Páyvar. This was his second opportunity to study under maestro Páyvar. He considers this period of learning as the pivotal point in his musical life, which enabled him to find his own path in the world of Persian music.

During this time, he shared his musical findings, compared numerous radifs and further sharpened his performance skills with maestro Páyvar.

Although Khayat assembled the Ney-Dávood Orchestra ensemble in Los Angeles for a short time, intending to preserve, promote and render Classical Persian music in its pure form, he arrived at the conclusion shortly thereafter that the integrity his musical quest of Classical Persian music was being compromised for fame and fortune.